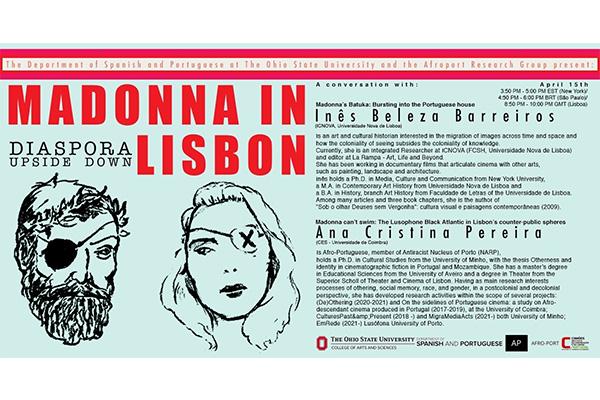

The Department of Spanish and Portuguese and the Afroport Research Group (Portugal) present the third season of the lecture series Madonna in Lisbon: Diaspora Upside Down. We will feature two speakers on Friday, April 15th, between 3:50PM-5:00PM in this remote event held on the Zoom platform. Attendees should register here:

https://osu.zoom.us/meeting/register/tJwrce2hpz8qEtX7XS6ZurfmiRGzZ6bhMeLa

Madonna can't swim: The Lusophone Black Atlantic in Lisbon’s counter-public spheres

Ana Cristina Pereira (CES-Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal)

"Can't swim/não sabe nadar" is the chorus of the first Portuguese RAP hit (1994), and contrary to what it may seem, the phrase creates community among all those who can't swim. Batuka could be a cliché. However, given the difficulty of covering themes such as slavery and colonialism in Portugal, this video places Madonna on the side of those who cannot swim the murky waters of the “Portuguese sea”.

Opening Batuka’s video, the sentence: “Batuque is a style of music created by women in Cape Verde, some say the birthplace of the slave trade.” Then, starting the music video itself, an image of a group of caravels in the sea, as if they were ghosts of caravels. The women, on land, see them fearful. At the end of the video, the same sea, still seen from the ground, with the same caravels, supposedly moving away.

This explicit association between caravels and slavery is not common in Portuguese mainstream pop culture, nor is Cape Verde associated with the idea of the transcontinental trade in human beings. In the mainstream discourse, caravels continue to be an unblemished symbol of the discoveries' grandeur, and Cape Verde is the best example of the exceptionality of Portuguese colonialism. Nerveless, even if made invisible and erased by the hegemonic discourse, the map of the slave routes is ghostly present today in the Portuguese counter-public spheres.

After the 1974 revolution that brought Salazar’s regime to an end, Portugal (re)adopted its adhesion to the European Union as a national project, intending to project itself onto a “white, developed, and cultured Europe”. However, the Portuguese Black counter-public spheres are constructed through the triangulation of influences from alternative models of thought and action, coming mainly from Brazil and several African countries. Not by chance, this intercultural network reproduces routes of the Atlantic slave trade.

The Portuguese language is a legacy of the colonizer common to new travelers on these routes. It is a mark of the historical violence to which they were subjected, but like the routes they travel today - which are projects of freedom, not just resistance - the language is appropriated and re-signified. Furthermore, contrary to Paul Gilroy's (1993) image that presents the Black Atlantic as a male experience, the Lusophone Black Atlantic is womanist.

Starting from the ghostly images of caravels in the “Batuka” video, I will reflect on the (re)organization of Portuguese Black counter-public spheres and on the difficulty of deepening the discussion on colonial legacies in a country caught between imperial nostalgia and its strive to belong to a “superior and whiter” Europe.

Madonna’s ‘Batuka’: Bursting Into the Portuguese House

Inês Beleza Barreiros (ICNOVA, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal)

In one of the initial shots of the music video “Batuka” (2019) that Madonna co-created, in her Portuguese exile, with Orquestra Batukadeiras, we see black women bursting into a house and inhabiting it. That house is Casa Branca [White House] that architect Raul Lino (1879-1974) built, in 1920, for himself and his family in Azenhas do Mar. Nevertheless, we are led to believe we are in Cabo Verde, “some say the birth place of the Slave trade.” Lino designed this house according to the “simple building” precepts he theorized in A Nossa Casa (1918) [Our home]. Its argument would later be developed in Casas Portuguesas (1933) [Portuguese Houses], which was appropriated and misused by Salazar’s regime, at the dawn of the dictatorship, as if, contradicting the plural in the book title, there could be just one Portuguese house and one Portuguese way of living. In reality, Lino’s Casa Branca, a kind of Greek-style promontory in the steep ridges of Sintra’s coastline, is inspired by the hut Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) built for himself around the shores of the Walden Pond, in Massachusetts, where the philosopher spent two years living “a simple life”, while refusing to pay taxes to a Slave State that on top of that promoted wars with Mexico. He would narrate this experience in Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854), Raul Lino’s bedside book. Nowadays, the image of Lino’s house is often included in Portugal's tourist promotion materials, in brochures and videos intended to attract an international audience to “Europe’s West Coast”. It is a kind of ex-libris, often photographed and shot from the point of view of those who are inside the house looking outwards at the sunset. In many ways, “Batuka” is its reverse shot.

Based on Madonna’s music video “Batuka”, I will explore these past and present ramifications, highlighting its tension points and exploring how these initial shots of black women bursting into this “Portuguese house” might constitute a metonymy for the current cultural discussions in Portugal, when more and more racialized subjects question the lusotropical status quo, take position, and demand their right to be recognized as fully Portuguese. “It’s a long road” and Madonna saw it coming.

If you require an accommodation such as live captioning to participate in this event, please contact Pedro Pereira (pereira.37@osu.edu). Requests made two weeks before the event will generally allow us to provide seamless access, but the University will make every effort to meet requests made after this date.